Princeville: The First Black Town to Incorporate in the United States

The North Carolina DEQ's diversity and inclusion group took a tour of Princeville and posed in front of the museum.

Photo: Rona Kobell/EJJI

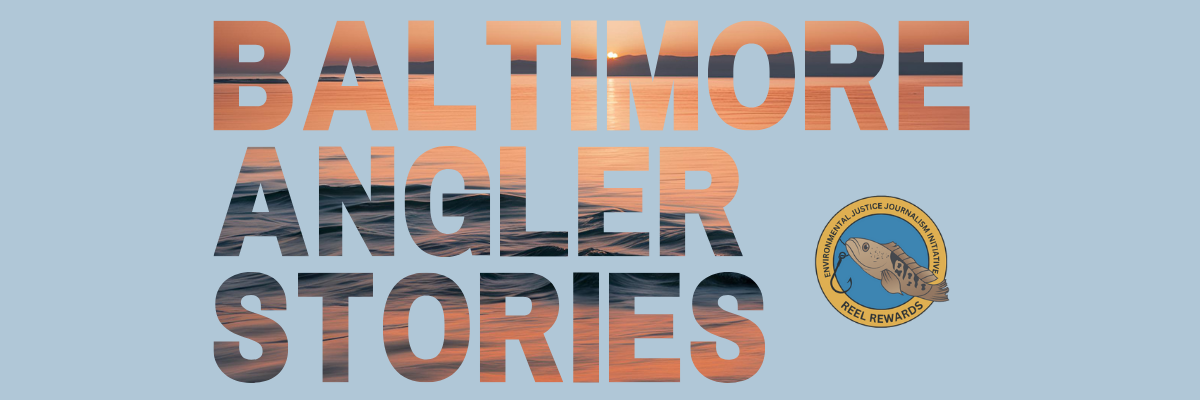

Dr. Glenda Knight, a longtime Princeville resident and board member, is now the town manager. She is committed to building back the town "bigger, bolder and better."

Photo: Rona Kobell/EJJI

Princeville residents are proud of their history, and the mobile museum shows that.

Photo: Rona Kobell/EJJI

Linwood Peele, a longtime manager for the North Carolina Department for Environmental Quality, points out where flooding had occurred in the past in Princeville.

Photo: Rona Kobell/EJJI

Princeville: The First Black Town to Incorporate in the United States

By Rona Kobell

Princeville sits just off U.S. Highway 64 in North Carolina, where the Tar River meanders through cotton fields and strands of loblolly pines. The town of about 2,000 residents appears unremarkable at first glance – bungalow-like homes, some empty farmland, and no grocery or courthouse or central business district to anchor it. Many drive through and do not realize they are passing history.

This 1.5 square mile town was the first Black town to incorporate in the United States. It did so in 1885, just 20 years after a group of formerly enslaved Black families settled in the area they first called Freedom Hill. Even now, more than 150 years after the Civil War, the United States can boast many towns with large Black populations but few incorporated Black towns. Maryland has only three: Highland Beach in Anne Arundel County and North Brentwood and Eagle Harbor in Prince George’s.

What incorporation gives a town is the ability to control its own destiny. An incorporated town elects its own officials, collects its own taxes, crafts its own zoning laws. Its leaders can decide what areas become developed, what must remain in green space, where to put the elementary school, and what aspects of the town to highlight for visitors. Incorporated communities can lobby the state legislature for bond funds and nonprofits for grants. They can control the look, feel and survival of the community. When Princeville’s founders won incorporation, they inherited a gift they passed on to their children. It has been the gift of survival.

Like many Black communities, Princeville only got the soil it sits on because no one else wanted it. The land is low, about 40 feet below the highway that traverses it, and far lower than its sister town across the river, the much wealthier Tar-Boro, which is the Edgecombe County seat. And so, the community floods – a lot, more than a dozen times between the time it was founded and 1967, when the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers built a three-mile earthen levee. The levee held pretty well until 1999, when Hurricane Floyd inundated Princeville and nearly wiped it off the map.

State officials hoped to relocate Princeville two miles up the road on higher ground, but the community voted to stay. Since then, the residents and leadership have been looking at ways to fortify the town. Expanding the levee would be a great solution, but with the Corps not quite sure what route they are taking community leaders are doing what remains in their control. Because of incorporation, that’s quite a bit. They’ve secured grants to build rain gardens, plan for a commercial district on land outside the floodplain, reinforce the town hall and lift some buildings. They have Black leadership team and a town historian who is helping apply for grants to honor the town’s story. They have entered into partnerships with North Carolina State University to help with resiliency. A mobile museum tells the Princeville story with just a few pictures and quotes, but it is powerful.

EJJI was invited to tour Princeville with state officials from North Carolina earlier this month. After that, we were on a panel with leaders from town to talk about ways the North Carolina Department of Environmental Quality can be more inclusive in their outreach and their regulations. Among the ideas we shared: hold meetings whenever possible in communities, in the evenings, and not on Wednesday nights (a popular Bible study evening). Also, matching grants for funds exclude communities that can’t raise that money, and favor the wealthier white communities that can. We also spoke about land-conservation programs that favor large tracts on higher ground that are threatened by development, which many Black families couldn’t buy. Maybe look at a provision for historical and cultural assets?

The trip was a reminder of something EJJI tries to reinforce: environmental injustices take many forms, and they are all rooted in the history of systems designed to oppress religious, ethnic, and racial minority populations and keep them marginalized. Sometimes it’s obvious, such as an incinerator in a Black community; sometimes it’s not, such as the lack of incorporated Black towns in the United States. But without control of your destiny, you cannot preserve your culture, and you would be unwise to leave those decisions in the hands of those who never honored that culture to begin with. As the Washington Post’s excellent DeNeen Brown points out in this article from 2015, no archive exists of all the nation’s Black towns. White historical societies simply didn’t think to hold on to the records, and the people making history were often too busy trying to live under oppression to write everything down themselves. Thus, the histories of Blackdom, New Mexico; Rentiesville, Oklahoma; and Nicodemus, Kansas, are not complete.

But Princeville’s is, and we can thank the ancestors for that. For more about the “town that defied white supremacy," check out the town’s history here.